Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

Paradise On the Big Screen

The Indus River

“… one of us did the cussing, the others prayed.” — Don Hatch

July 11, 1956.

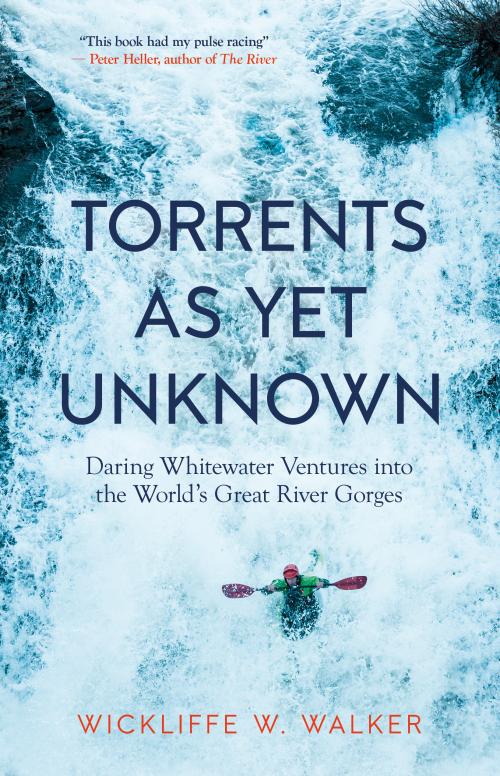

From a precarious jeep track hundreds of feet above the white torrent, the Indus River appeared bigger than anything Bus Hatch had ever attempted to raft. Probably bigger than anything anyone had attempted to raft. Barren khaki hillsides rose thousands of feet in all directions, rocky ribs exposed above slopes of scree and tangles of low bush so brown as to appear as hard as the rock itself. And just over that immediate horizon, unseen but nevertheless a dominating presence, loomed the icy summits of the greatest mountain ranges on Earth: the Karakorum, the Himalaya, and the Hindu Kush, pumping their glacial meltwater into the Gorges of the Indus.

Less than a month before, the phone had rung in the dusty, cluttered office of Hatch River Expeditions in Vernal, Utah, and the operator announced a call from New York. Bus Hatch, age 56, stocky but athletic, his deeply tanned face accented by round wire-rimmed glasses and gray stubble, listened intently to the voice on the other end of the line, perhaps the best known voice in the English-speaking world, as the caller made an audacious proposal. Bus spoke little, jotted some notes, and in the end, said yes. Replacing the handset in its cradle, he immediately dispatched a substitute trip leader to pull his oldest son Don off a raft trip down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. Then Bus asked if anyone in the office knew where Pakistan was. The young country had been part of India when he went to school.

Now Bus had his answer. At the end of the road for the jeep, in a tiny village named Gol, Bus, Don, the expedition’s leader Otto Lang and Pakistani Army liaison officer Captain Alim prepared their equipment for a launch early the next morning. Their attempt, if successful, would be the first known whitewater run in the Himalaya. Hired village laborers spent hours hand-pumping an enormous inflatable raft that was twenty-seven feet long and seven-and-a-half feet wide. One wooden platform spanned the center for an oarsman, another on the stern mounted a 10 horsepower Johnson outboard motor. Lang and Captain Alim had no idea what to expect. Bus and Don Hatch did — perhaps.

The launch point onto any river is a special place. A place to abandon the road, or trail, or whatever line on the map leads back to home and family and origins. A place to commit to the current that flows but one direction — into the future. And when that future cannot be known — not the course of the river, nor its dangers — then the put-in is also a place of fierce anticipation, of dread suppressed, of the copper taste of adrenaline. A place of voices too loud, jokes too hearty, the bustle of loading boats exaggerated. The urge is overwhelming to relieve the tension through action, to launch, even if it is just to round the next bend and establish the first camp. Yet this gravid moment of anticipation is also one of the most intense in any explorer’s lifetime, a moment to drink in and savor.

The team launched at 6:45 a.m., and the power of the Indus shocked even the two whitewater pros. Estimating the size and difficulty of rapids from hundreds of feet above is notoriously difficult. The Hatches knew this, of course, even if their companions did not. But the eye sees what experience leads it to expect, and in the Himalaya, just as the respiratory system must acclimatize to the thin air over a period of weeks, so too must the eye and brain adapt to the titanic scale. Legendary British climber and explorer Eric Shipton articulated the dynamic in this description from the early days of his landmark 1934 exploration of Nanda Devi with H.W. Tilman: “… I was not yet used to the immense scale of the gorge and its surroundings. Tilman suffered from the same complaint. We also had great difficulty in judging the size and angle of minor features. …. However, the eye gradually adjusted itself, and soon we began to move with more confidence.”4

The glacial melt waters of the Indus thundered through the canyon at roughly four times the volume of the Colorado Bus and Don were used to, perhaps a hundred thousand cubic feet per second, and the rapids were steeper and more continuous. As always when nature challenged them, the Hatches deployed their prodigious river skills and cowboy humor. They gritted their teeth, but also cursed and laughed to inspire confidence in their nervous passengers.

At one of the rare calm eddys*, beyond which the river narrowed and thundered ominously over a sheer horizon line and plumes of spray shot skyward, evidence of the chaos below, the crew stopped and stepped off the raft for a scouting mission. Edging downstream along the rock wall, Don was dismayed to see the entire river split around a huge boulder, then plunge about twenty-five feet in less than thirty yards, careening into the cliff wall on the right and creating a violent recirculating eddy on the left. But they re-boarded, and went for it.

As the raft hit the point of commitment, Don revved the outboard motor, and they accelerated down the tongue of racing water, “like flies on our way to the sewer.”5 In the massive white recirculating hole* at the bottom, the raft folded on itself, launching Lang backward into Don and almost knocking both over the stern. Half full of water, the raft careened toward the rock wall on the right, rode high on the massive pillow of water piling against the cliff face, then slithered along the escarpment to the pool below.

Later that day the raft and its exhausted crew drifted out of the narrow canyon to the wide, flat river by the regional center at Skardu, gateway to the Karakoram mountain range and connected to the rest of Pakistan only by caravan trails and a short military airstrip. Otto Lang cabled back to New York:

BUS AND DON HATCH MADE THE FIRST DESCENT OF THE INDUS

GORGES FROM A POINT THIRTY MILES ABOVE SKARDU STOP I WAS

MERELY A WIDE-EYED PASSENGER AND HAVE RARELY WITNESSED

SUCH A CATACLYSMIC FORCE OF NATURE, ONLY COMPARABLE TO

BEING SWEPT AWAY BY AN AVALANCHE STOP 6

Ironically, no film was shot of that momentous day. Ironic because the expedition for which Don and Bus had been recruited was part of a film shoot. Otto Lang, an immigrant to America from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, had parlayed his status as the ski instructor for Hollywood’s elite into film directing opportunities. His team had brought with them to Pakistan the most sophisticated movie cameras of the day, and they were there at the behest of the most famous documentary filmmaker of his generation. No explorer had ever before attempted to raft the remote, gigantic rivers of the Himalaya. The unprecedented effort was the brainchild of Lowell Thomas, the voice on the other end of that telephone call Bus had received from New York just a few weeks earlier.

Thomas was an incongruous product of the rough-edged gold mining boom town of Cripple Creek, Colorado. His father, a medical doctor and polymath scholar, drilled into him from childhood the formalities of elocution and oratory. He first made his reputation as a documentary filmmaker and adventure travel celebrity by tracking T.E. Lawrence across the deserts of Arabia during World War One. In the words of Lawrence biographer Malcolm Brown, “Thomas breathlessly portrayed Lawrence’s exploits in Arabia through films, radio broadcasts, and print to an audience hungry for victories and heroes during the dark days of the war.” He almost singlehandedly created the legend of “Lawrence of Arabia,” to the introverted scholar’s dismay. The flamboyant Thomas emerged from the war in the front ranks of American documentary filmmakers.

In 1930 the young Columbia Broadcasting System aired Thomas’s nightly news program, the country’s only national radio news show. With his resonant voice yet apolitical, folksy style, he maintained his preeminent position for four decades, with his show moving from CBS to the rival National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and back to CBS again as the news industry grew up around him. His nightly audience was estimated in 1936 to be twenty million, from Canada to the Caribbean. Soon after, Fox Movietone News made him the voice of newsreels in fifteen thousand movie theaters as well.7

In the small, clubby society that existed between the world wars, it seemed that Thomas knew personally everyone that mattered. At his elegant 500-acre farm estate on Quaker Hill in the New York Catskills, with its Georgian thirty-two-room mansion house, the political, social, and business elite rubbed shoulders with professional athletes, artists, and European aristocracy. Thomas organized a softball team of neighbors, and visitors like World War One ace Eddie Rickenbacker, world heavyweight boxing champions Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey, Yankees slugger Babe Ruth, author Dale Carnegie, General Jimmy Doolittle, and New York governor Thomas E. Dewey, for friendly grudge matches against a team that was managed by Franklin D. Roosevelt and composed of the staff, correspondents, and Secret Service detail from his nearby Hyde Park estate. “Ike” Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Sam Snead played Quaker Hill’s private golf course. Europe’s and America’s top alpine skiers congregated on its ski hill.

Eagerly embracing air travel from the earliest days of commercial aviation,

Thomas was “jet set” before the jet was invented. No place was too remote, no kingdom too forbidden. He had the connections to wangle invitations and expedite travel for himself and his camera. He toured India with the Prince of Wales, flew to both poles, rode horses over the Himalayan range to Lhasa to visit the Dalai Lama, rode camels across the Sahara to Timbuktu, drove over the legendary Khyber Pass to meet with King Amanullah Khan of Afghanistan in Kabul.

By the 1950s Thomas was heavily invested in a new movie-making technology, Cinerama — the IMAX of its day. Utilizing a camera that shot simultaneously through three lenses, the film was then projected on a custom-installed curved screen that wrapped 146 degrees around the front of the theater and combined with stereo sound to produce something of a three-dimensional, immersive effect.

When he found himself appointed by President Eisenhower to represent the United States at the coronation of a new King of Nepal in May, 1956, Thomas rightly foresaw that this might be a final display of vanishing oriental splendor in the rapidly modernizing and globalizing world. He determined to use the occasion to showcase his new technology by displaying the exotic grandeur of the Himalaya and South Asia. Unlike his previous documentaries and travelogues, his chosen vehicle this time was to be a dramatic feature film, Search for Paradise, a loosely scripted story of two former American airmen travelling the world in search of adventure and fulfillment.

In addition to the coronation scene in Kathmandu, a polo tournament in Hunza, exotic temples in Ceylon, and the legendary houseboats of the Vale of Kashmir, one highlight was to be a whitewater adventure (initially to be kayaking, later changed to rafting) where the mighty Indus River carves a cleft between the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges of Pakistan. In 1956 there had been no known whitewater expeditions anywhere in the region, and Lowell Thomas did not know the first thing about rivers or whitewater. But he did know how to find his Lawrence.

He recruited one of his skiing pals, former Dartmouth Outing Club ski racer and pioneer Colorado kayaker Steve Bradley, to fly to Northern Pakistan and scout the river in advance of the film crew. At the historic Flashman’s Hotel in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, Bradley briefed director Otto Lang on the enormity of his task. Kayaks in 1956 were still European adaptations of the arctic hunting boats: a rubberized canvas skin stretched over a wooden frame. Neither the kayaks nor the paddlers’ skills of the day were remotely capable of withstanding the crushing power of the rivers where Lang and his crew were heading. And mounted with the massive Cinerama camera, the lightweight raft Lowell Thomas had shipped out from a New York sporting goods store could barely stay upright in the hotel swimming pool. Before flying back to the States, Bradley advised Thomas that their only hope for success might lie with the legendary river runner Bus Hatch.

Born into a pioneer Mormon family in Vernal, Utah in 1902, Bus grew up a skilled hunter, fisherman, boater and general outdoorsman. He acquired his self-taught whitewater skills through passion, rawhide toughness, and luck, and when he first ran the Grand Canyon of the Colorado in 1934, in a wooden dory he had designed and built himself, he was one of the first fifty to do so since Major John Wesley Powell in 1869. Bus was gruff, daring, and self-sufficient. He expected those around him to be the same. Quick to anger when others did not equal his skill and nerve, he also met physical adversities — from wrecking a boat to running out of food or being caught in a winter ice storm — with dry western humor. Crewmen with thick enough skin to stay on with him were intensely loyal.

Initially, fellow river runners were few, and the fragile wooden rowboats used to shoot whitewater rapids were ill suited to the task. The end of World War II, however, brought to market a bonanza of war surplus rubber assault boats, and huge twenty-seven-foot pneumatic pontoons from the floating bridges that conveyed the Allied Armies across the rivers of Europe. Bus was quick to appreciate the utility of both on the big, fast rivers of the American West, and he soon had them rigged into craft that could carry not just himself and his fellow rivermen but passengers as well. By the mid-fifties, Hatch River Expeditions, run by Bus, his sons and other family members, was the premier outfitter taking groups down the Green and Colorado Rivers, the Salmon in Idaho, and other major western rivers. Bus had no peers in big whitewater . . .