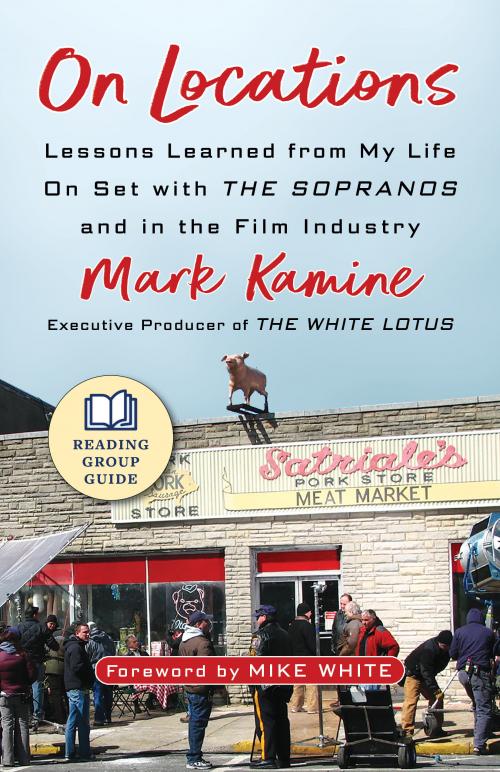

Excerpt

Foreword

Throughout my career, I’ve had bad experiences with line producers. It’s not always their fault. They must play the role of the in-house heavy and their job is to tell me when I’ve asked for too much. I can handle a “NO” (mostly) but sometimes I find the manner in which the ‘NO’ is delivered to be unforgivable. If she defends her ‘NO’ with only mumbo-jumbo about budgets and studio mandates, I lose all trust. Does this philistine care only about the bottom line? What about art and my vision? For this sequence to work, I need 200 extras and the yacht to explode — don’t you get it, you traitorous myopic weasel?

Mark Kamine came into my life, I don’t exactly remember when. It was a job interview and he seemed affable enough — he said all the right things about my script, and how his job is to support the director, yadda yadda — but I didn’t trust him — because I’m a junkyard dog and I wasn’t born yesterday, and line producers are shady as Hell. I got home and began my due diligence with a Google search, and to my confusion, up came a bunch of inarguably well-written book reviews. A line producer who is also an astute reader of literature — and a great writer himself? This can’t be the same Mark Kamine. But it was. I haven’t worked with another line producer since.

Mark and I have shared some amazing experiences in the last few years. Maui at sunset, drinking cocktails — made by his wife, Tana — the only guests of a giant, fully-staffed hotel. Dinners in Sicily, watching Mount Etna shoot red lava into the night sky. Location scouts that extended into “atmospheric pilgrimages,” touring some of the most picturesque spots in Japan, Thailand and France. We have shared moments of pain, too — crazy long hours, insufferable actors, angry network calls. But even in the darkest moments, I have never lost my trust in Mark. It really does help to have a fellow writer minding the store. When he says “NO,” I sense it pains him more than it does me. I still go back to my hotel room cursing his name, but it takes the edge off.

It’s not just with me — Mark engages everyone with a writer’s curiosity and respect. He knows we are all heroes in our own stories — and therefore, treads lightly and kindly as he goes about his job, careful not to become someone else’s villain. I love him for that — and this reminds me of my one quibble with this book. In it, he says the showrunner — and perhaps a few of the actors — are crucial to the creative enterprise. Everyone else, including him, is replaceable. I disagree. Not to get too airy-fairy, but I believe that the art reflects the collaborative, alchemical spirit in which it is made. Mark is a leader of our show, and his humanist outlook — born of his writerly mind — is essential to the final product, and I am grateful for it.

There is one downside to having a writer in his position — a creeping suspicion that Mark is taking notes, and will one day bear witness to all that he’s seen. After reading this great memoir, I have a right to be paranoid. When I’m an asshole — or an idiot — or a pretentious artiste who demands 200 extras and an exploding yacht, I can now assume it will all be revealed in the follow-up to On Locations. But it’s a price I’m happily willing to pay.

Mike White

Thailand

April 2023

1 My New Jersey Family, Part One My father’s wife, Grace, calls me about my father. This is a few years before I meet my wife, Tana, before I go to film school, before I start working in the biz, but after I’ve come through the severest period of anxiety attacks and agoraphobia that hit me in my early twenties. It’s 1986. The conversation below, as with all the conversations in this book, is an approximation, some of it clear in my mind, some the result of a conviction of proper pace and meaning, some simply my best guess.

After we say hello, Grace asks, “Do you think you could come out and talk to your father?”

I am surprised and to some extent put on guard by this. We aren’t estranged by any means. I get invited to occasional sporting events and dinners and, more regularly, holiday parties. But clearly this isn’t that. We don’t have a stop-by-without-occasion relationship. I’ve never been asked to come over to, simply, talk. In truth we don’t, my father and I, in any substantive way, talk.

“What’s up?” I say.

“He’s having a hard time.”

“Meaning…?”

“Well, he’s not getting out of bed.”

It sounds like she’s talking about a kid sick with the flu, not my father, longtime forceful, often silent, and usually serious straight shooter who came up on the working-class east side of Paterson, New Jersey, went from there to college, to Korea, back to college then on to law school, and now lives on top of a desirable hill in Wayne, the suburb west of Paterson where I grew up. He was a distant and sometimes strict parent with a solo law practice, played catcher on a scarily intense adult fast-pitch softball team, and drove indefatigably anytime we went anywhere. He hasn’t, in my awareness, changed much. I don’t know what to make of what I’m being told. I assume that my recent experience with anxiety and analysis bears on my being asked to come talk to him. It makes me the family expert on — on what? Sudden descent? Incapacity? The options for treatment if you can’t figure out how to get yourself out of bed?

“How long has it been?” I ask.

“Two weeks,” she says.

“Wow.”

“Yeah.”

“Anyone have any idea what it’s about?”

“I sure don’t,” she says. “He doesn’t seem to.”

“Got it,” I say. “I’ll come by. I’ll try to get there tomorrow. I’ll get there tomorrow. I’ll let you know when.”

“Tomorrow would be good.”

I borrow a friend’s car and drive out. Grace opens the door almost instantly. She thanks me for coming and waves a hand in the air, indicating upstairs. “In bed like I said,” she says. Then she says, “Archie! Mark’s here!”

She nods me up.

And there he is, lying flat on his back on the big, canopied bed, head elevated by a couple of pillows, eyes wide and unblinking.

“Hey, Dad,” I say. “What’s going on?”

He says nothing, looks at me with the wide eyes.

“You want to talk about it?” I ask. “Grace said you’re having trouble getting out of bed.”

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” he says.

“There’s nothing physically wrong? Is that what you mean?”

He nods. “I don’t…I can’t get up,” he says.

“Okay, you’re, you’re not feeling good. It feels, what, like you’re weak” — I am watching him closely and he gives the slightest shake of his head — “or maybe more like it’s pointless?”

This conversation is going slowly. This is the way it happened: Him in his bed, under the covers, head propped up. Me standing at the end of the bed looking down at him. I have rarely been in their bedroom. The first time was when they gave me the tour after they first moved in, rightfully proud. It’s a beautiful house. A big, beautiful bedroom, big windows looking out over trees and a distant lake, a spacious bathroom through an area of walk-in closets.

“Like there’s no point to…anything?” I say.

No response.

“Grace said it’s been a couple weeks,” I then say.

“Yeah,” he says.

“Did anything happen a couple weeks ago? What happened recently?”

“Nothing, really,” he says. “I put forty grand down on an office condo on the Turnpike. To move the office to.”

He has been renting three rooms in a low-rise office building in a strip mall parking lot a few miles from his house. The first time I saw the strip mall space, which by this time he’s been working in for several years, I was crestfallen. The rooms were small. His secretary mostly worked at his big desk in the main office and he spent his time at the short conference table in what he called the library, where I built him a wall of dark-wood bookshelves to lend the place a legal flavor. I was not a great carpenter. I did all right with the shelves, but the office had a cramped, fluorescent-lit, cheaply constructed feel and the shelves loomed over the conference table with threatening weight. When I saw what they looked like — dangerous — I attached numerous angle irons to the underside of every other shelf to anchor the structure to the wall. His prior office in Paterson, before his move to the strip mall, had been in a grandish Federal-style building, smoked glass with his name in black letters on the entrance door, big rooms with marble columns half sunk into the retrofitted plaster walls, big windows looking out at a real city. The strip mall office looked across a parking lot to Wayne Valley High School. I couldn’t blame him for wanting something nicer.

“And now you don’t want to move the office there?” I ask.

“I signed a contract,” he says. “I mean what if I…what if I can’t work. I used Nicole’s college savings for it.”

Nicole is my half sister, twenty years younger than me.

“Maybe you can get out of it.”

“I signed the contract.”

“You could ask, though. People understand.”

“I could ask.”

He doesn’t seem sure about it. He’s looking at me.

“Can’t hurt,” I say.

“No,” he says.

“So,” I say. “So, what do you think’s going on?”

“I think Grace is gonna leave me if this keeps up is what I think,” he says. “I mean, how much of this will she put up with?”

“I don’t think she’s leaving you. More like she’s concerned about you.”

“I mean, what’s wrong with me? It’s pathetic.”

“Well, as you know with what happened to me, these things happen. I mean you took me to the doctor those first couple of times I had panic attacks. And I couldn’t leave the house for a while. Like, I got panicky anytime I went anywhere.”

“Yeah, you weren’t in good shape.”

“The therapy helps,” I say. “Talking. I mean the Valiums didn’t hurt, either.”

“I don’t think I can do therapy,” he says.

“No?”

“It’s not me,” he says.

I resist the obvious, This isn’t you, either. Instead, I say, “Okay. But maybe you should talk to someone. I mean a friend. What about, I don’t know, John would be a good person to talk to I bet. He’s seen tons of this, I’m sure. Actors, right?” I smile.

My father lies there, eyes on me.

John is married to my father’s wife’s sister. He was in an experimental theater company in the 1960s and early 1970s, performing at La Ma Ma and other downtown theater spaces. Their plays had lots of energy, profanity, bawdiness. At some point John’s company hooked up with the Public Theater, where they performed their own stuff and whatever came along. Their regular director started mentoring John and eventually handed his baton over on one of their bigger shows, a Broadway revival of The Pirates of Penzance. Now John is directing plays and is starting to get into three-camera TV, soaps and sit-coms. My father loves being a sometime part of his world, and in return invites John to his club. They play tennis, have drinks and dinner. John is easy to talk to.

“I could,” he says.

“Sure,” I say. “Call him. Talk about how you’re feeling. Or just tell him how you don’t feel like doing anything and see where it leads.”

“Need to do something,” he says. “She’ll leave me if I don’t.”

“I’m sorry you’re going through this, Dad,” I say.

“Your grandfather had these things, I remember. A few times. He’d go into a black hole. For months sometimes.”

“Really?” I say.

I’d never heard this. His father, my grandfather, is steady, healthy, active. Eighty, still sharp, drives himself all over, lives in the senior apartments not far from his son’s office, still fills in at the counter at Tabatchnik’s delicatessen, where he used to work.

“Like a cloud came over him,” my father says.

“Runs in the family, I guess,” I say.

This gets a smile from him.

“You saying we’re all cracked?” he says.

This gets a smile from me.