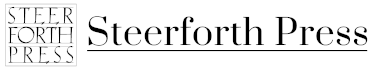

Excerpt

Chapter One

War and Peace

I retired when I was 28 years old, but ran out of money the same afternoon, so I caught a bus to the dole office. My feeling about unemployment was: someone’s gotta do it. Why not me? The pay was lousy but I’d heard the hours were good.

I had been working for the past 16 years – driving buses, washing dishes, picking grapes, packing boxes, building exhibitions and, once, digging the same trench for three days before someone told me I was digging in the wrong direction. (Subconsciously, I think, I’d started digging for home.) I was fed up with the whole racket.

At the Centrelink office I learnt that it was no longer called “the dole”. Some overpaid marketing agency had rebranded it “Newstart”. The walls were covered with inspirational posters (“When opportunity knocks, open the door!”) alongside more practical advice telling us not to drink alcohol before job interviews. Fake nails clacked away at keyboards. Someone called my name and I followed him into a small room. I hadn’t even sat down before he started trying to sign me up for forklift-driving jobs on the other side of town.

“Whoa,” I said. “This isn’t the kind of Newstart I had in mind at all.”

I had only just moved to Melbourne. It seemed like a place filled with magic and possibility. I wanted to meet interesting people at rooftop bars. I wanted to read Russian novels. What I didn’t want was a pesky job, but try telling that to your dole officer.

“Listen,” I said, “our economy seems to rely on a 5 per cent unemployment rate. Can’t I just be one of those 5 per cent for a while?”

The long answer was no.

People, I’ve found, want you to be busy. They don’t require you to contribute anything meaningful, otherwise how do you explain professions like “consultancy”? They just want you to be busy. Genghis Khan could move into your street and people would say, “Well, at least he’s working.”

My dole officer changed tack. He straightened his tie and wafted some cologne in my direction.

“What about truck driving?” he said. “I’ve got some great truck-driving jobs.”

I’d spent the previous three years driving tour buses in the outback. One morning it had been so hot that I woke up with a lisp. I had a crooked back, was still finding sand in my underwear, and harboured some latent racism (mostly against the Swiss) that I was trying to deal with. I was sick of driving. But you can’t just come out and say that.

“What sort of loads would I be carrying? I’m allergic to peanuts.”

“Furniture,” he said, eyeing me suspiciously. “No peanuts.”

I held in my lap my talisman copy of War and Peace. I had vowed not to get a job until I finished reading it. But the dole officer had obviously sworn some oath of his own. He was so dogged I was amazed he hadn’t risen through the ranks yet.

“Is it far away?” I asked, eventually.

“Just around the corner.”

“Oh. That could make things difficult.”

“Difficult how?”

“Well, I was thinking of moving.”

*

What followed was a series of long and glorious autumn days. I wandered through parks, galleries; I winked at old ladies, had long boozy dinners in friends’ backyards.

My uncle was in town one day, and I explained that, what with the demands of War and Peace and everything else going on, I scarcely had time for a job.

“Well, it’s a question of priorities, Robbie,” he said.

We looked at each other and I hit the table with my fist. “Exactly.”

When my second appointment came around, the dole officer asked me how I was getting on, and I told him about the projects I was working on. He made a few notes.

“So, you’re writing a book?”

“I’m reading a book.”

He became businesslike. He said that, as per regulations, I was to start filling out a job diary and applying for 20 jobs a fortnight. Twenty!

It was even more odious than having a job. It sounded like I would be doing a lot of extra work, so I asked him for a pay rise.

His answer was long and wearisome, like your primary school teacher going on and on about not eating pencil shavings.

Eventually I pointed at the job diary and said, “But. But what’s the point of it?”

The point was “How dare you!” The point was “We the taxpayers!” etc.

Andy, my friend and housemate, had little sympathy. “They pay you $230 a week for doing nothing.”

“I don’t get the money,” I said. “Our landlord gets it.”

“Oh, not this again.”

“Well, I work just as hard as he does.”

“Not today you didn’t.”

“It’s a Saturday, Andy. Jesus.”

“Not yesterday, either. You spent all morning trying to glue your boot back together.”

“Okay, so we happen to have a particularly hard-working landlord. But morally…”

You have three months, by my calculations, to explore a city before your sense of wonder turns to familiarity. I used to board trams with excitement, thinking, Where will I possibly end up? Now I knew exactly where. As the days shortened, the trams ploughed the same old furrows up and back, and I rode with them.

The pay, I was learning, was barely enough to make rent, let alone have the wild times that welfare recipients are always having on the news. And not even the hours were good! There were meetings, job diaries, and you were constantly having to catch two buses out to Broadmeadows, and back again, to attend some 45-minute course on Time Management. It’s hard to understand what all this was in aid of, but the flourishing of the human spirit was not one of those things.

Time stretched out interminably. My reading was turning frequently into napping. I was languishing somewhere between war and peace.

Then, through a series of clerical errors and misunderstandings, I accidentally got a job as a dishwasher.

Every time I start a new dishwashing job, I can’t imagine why I ever quit. It’s exhilarating. You feel like a general, marshalling his troops. Waiters pile up coffee cups and teaspoons on one side, chefs drop hot pots and pans into the sink on the other, and you’re in the middle of it all, suds flying. At the end of a shift you have that physical tiredness that feels almost like a life well lived. On your lunch break, if you get one, you send out group text messages: “Friends! You were right! Maybe this is the answer!”

And then, after two or three shifts, you start to remember. The sinks are always too low, so you stoop all day, or all night, and wake up in the mornings, or afternoons, with a cracking headache. You get covered face to feet in grime. The kitchens are hot, cramped and almost always an insufferable boys’ club. If you’re new they’ll send you off to fetch a made-up item, like a “rice peeler” or a “bucket of steam”. (I would pretend to fall for that one and sit in the storage room reading a book until someone came looking for me.)

You become increasingly convinced that, in the world outside your kitchen, in some endless dusk, bands are playing on street corners, friends are having wild picnics, and everyone you like is sleeping with someone else.

It becomes harder and harder to contain the long, loud bouts of moaning at the helpless purgatory of it all. And shift after shift the dishes keep coming. You could work 15 years in that job and still have nothing to show for it. If you left the sink for one minute to accept your Golden Tea Towel Award, by the time you turned back the sink would be piled with dirties again. Worse, they’re the same dishes.

And dishes are as good as it gets, by the way. You need a biology degree to remove the oily film that clings to the inside of plastic containers. I had one, but for the wage I was getting I refused to use it. Sometimes I just threw dishes into the bin.

What sort of answer is this, to the question of what to do with our short time on Planet Earth? Sometimes I would find myself standing at the sink with my hands dangling in the dirty water, thinking, I can’t go on. It’s just too pointless. And dishwashing is one of the important jobs! Imagine how the consultants feel!

As soon as I smelled spring in the air, I quit the dishwashing and raced back to the dole office.

Somehow, impossibly, this dole officer was even more cunning than the last one. Within 10 minutes I was checkmated. He had the perfect job for me, he said. I didn’t understand all the details, but it sounded like I’d be working for a company that couldn’t afford a forklift, and was settling for me instead. I mumbled something about low blood-sugar levels and pulled some roast chicken out of my bag. (Not all victories can be won with dignity.) I wolfed it down and then pretended to choke on a bone. I writhed around on the ground, clutching my throat. The dole officer sighed, stood up and said, “We’re done for the day.” The man was no fool; he knew a piece of chicken breast when he saw one.

But also, it was 4.30 on a Friday afternoon. I lunged for the door. Not even the best dole officer in the land could catch me before Monday morning. I burst onto the street and sunshine hit me in the eyes as on the day of one’s birth. I did something similar to a yodel. I had two more days! Two more days in this world where, right now, a wheeling, chattering flock of rainbow lorikeets were shitting on someone’s scooter with what looked like pure joy. Two more days in this world where people play the bassoon, climb trees and help baby turtles get from their nest to the sea; where it’s possible to meet someone with whom to spend a lifetime watching wrinkles gather around each other’s smiling eyes. Two more days at least, before the vice clamped down on me once more.